One of the concepts that you will hear over and over in the literacy world is the notion that “print represents speech,” and that the only research-based approach to teaching reading and spelling is to start with the systematic study of phonemes — the segments in spoken language that are distinctive for meaning (often referred to as “sounds”) — and the way that we represent those phonemes with graphemes (often referred to as “symbols”). You will sometimes run into some debate over whether instruction for students should use a “sound to symbol” or “symbol to sound” approach, but it is taken for granted — assumed — that the relationship between those “sounds” and the “symbols” that represent them is the primary and central relationship between spoken and written words.

This assumption that print primarily represents speech is often stated as though it is a fact and may be followed by statements like this: “To read, we decode written words to spoken words, and to write, we encode those sounds of words into written form.” Any attempt to question this assumption is usually shut down quickly in many literacy communities as being “anti-reading science.” But in truth this is a theory, not a fact, and it’s demonstrably false, based on clear evidence in our writing system itself.

Every time you encounter a word that needs to be defined as an exception — a red word, a rule-breaker, a tricky word — you are being presented with evidence that falsifies the common assumption that spelling primarily represents the pronunciation of words.

There clearly IS a relationship between the spelling of a word and its pronunciation, but the evidence in the writing system overwhelming shows that the primary function of our writing system is not to represent pronunciation, but to combine units of meaning in consistent ways so that we can silently read and comprehend text. This sounds like it might be “whole-languageish” but it most definitely is not.

Let’s take a look at some evidence in the writing system that should help you evaluate the assumptions built into most literacy instruction. I’m not going to give you a counter opinion about this; I’m going to show you some examples of the spoken and written form of words, and let you decide for yourself whether it’s accurate to claim that “words are spelled based on the sounds we make when speaking.”

This next bit is dense going, and I’ve tried to make it simple as I can, but if IPA symbols are new to you, think about your own pronunciation of these words, and that should help the IPA symbols make sense.

So let’s look at these two words: <sculptor, sculpture>

There is clearly a relationship between these words; <sculpture> is a noun, often used to describe an object that was created by carving or shaping a substance; and the word <sculptor> refers to the creator of that object.

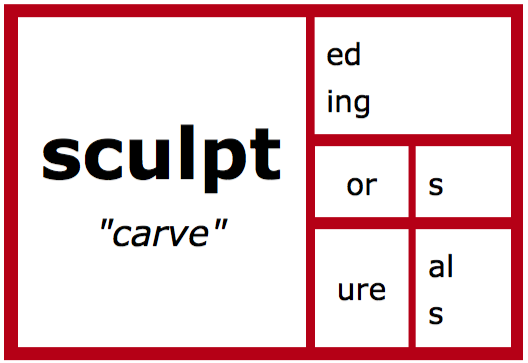

We can build a matrix which shows some of the words in the family related to <sculpt>. These words all have an orthographic denotation of “carve.”

Word sums show us the surface spelling of the words <sculpture & sculptor> on the left and the underlying elements we use to build them on the right.

sculpture ➞ sculpt + ure

sculptor ➞ sculpt + or

Now let’s analyze what happens to the pronunciation of the <t> in the base element <sculpt> in these two words.

First of all, think about the fact that the pronunciation of words can vary dramatically based on what part of the world you live in. If written language is speech written down, why don’t people spell words differently if they pronounce them differently?

In fact, we don’t do that, and to compare a word’s pronunciation to its spelling, we have to decide whose pronunciation we’re going to be working with. I’m going to base this on my own pronunciation, but think also about your own.

So we’ll start with a representation of my pronunciation of “sculptor” using IPA. These IPA symbols were designed to have a one-to-one relationship with particular articulations in spoken language. Here’s a representation of the phones in “sculptor” spoken with my American pronunciation:

[ˈskʌlptɚ].

Most of those symbols in [ˈskʌlptɚ] should make sense to you even if you are not familiar with IPA, but you do need to know that [ʌ] indicates the pronunciation of the <u> in <sculptor> or in the word <cup> or <sun>. And the final phone in my pronunciation of “sculptor” is represented by this symbol: [ɚ]. This represents the rhotacized schwa. Since I’m American, this phone represents the speech segment I articulate at the end of the word <sculptor>. Someone with a British accent would pronounce that differently. The rhotacized schwa appears in unstressed syllables when the schwa is followed in the orthography by an <r>. I produce the same pronunciation at the end of the words “mother, dollar, faster.”

You can pronounce those IPA symbols, [ˈskʌlptɚ], from left to right to approximate a neutral American pronunciation of the word <sculptor>.

So now let’s look at the relationship between the phones in the spoken word [ˈskʌlptɚ] and the graphemes in the written form <sculptor>. Clearly there is a relationship.

If we take the word “sculptor” we can see the correlations:

[ ˈs k ʌ l p t ɚ ] – (phones – representations of the pronunciation)

<s c u l p t or> – (graphemes)

Notice that there is a one-to-one relationship between the phones and the graphemes. So far, this seems to support the premise that written language is “speech written down.”

But now let’s look at <sculpture>.

We can represent the pronunciation of <sculpture> in IPA like this:

[ˈsk ʌlptʃɚ]

What has changed in the pronunciation between <sculptor> and <sculpture>?

You can see the IPA representation of those two words here, together:

[ˈs k ʌ l p t ɚ]

[ˈs k ʌ l p tʃ ɚ]

Notice that when comparing “sculptor” to “sculpture” the pronunciation changes from [ t ] to [ tʃ ].

[ tʃ ] is the pronunciation at the beginning of the word “chip.” It consists of two phones, [t] followed by [ ʃ ].

The change in the pronunciation of that <t> is similar to the change we feel at the beginning of the words “tip” and “chip.” You might pronounce “sculpture” slightly differently. Some people might feel that the second to last phoneme in “sculpture” is pronounced more like [ ʃ ] (as a the beginning of “ship”) than [ tʃ ]. That’s fine. That doesn’t change this observation.

So we’ve seen a change in the pronunciation of the <t> but notice that the spelling of the base <sculpt> does not change in these two words:

<s c u l p t or>

<s c u l p t ur e>

That same grapheme <t> is present in both words. It doesn’t change in the spelling of these words even though we pronounce that grapheme differently in the two words.

What changes in the spelling is the replacement of suffix <or> with <ure>. The spelling of that part of the word changes, even though my pronunciation at the end of both words is virtually the same.

(The <e> at the end of <sculpture> is not representing a pronunciation. It’s a marker letter.)

So when pronunciation of the <t> changes from [t] to [ tʃ ] or [ ʃ ], the spelling does not change.

When the suffix <or> is replaced with <ure> the pronunciation does not change.

Does this provide evidence that these words are primarily “encoded” sounds? Does it show us that written words are “speech written down?” It seems to show just the opposite. Aspects of spelling remain constant while pronunciation is shifting, and aspects of spelling change while pronunciation does not change.

So what is is going on, and what is driving the changes and stability of the spelling of these words?

Let’s take a look at the morphological structure of these words:

<sculptor ➞ sculpt + or>

<sculpture ➞ sculpt + ure>

You can immediately see that one part of the spelling of these two words is stable in both; the base element <sculpt>. This base element “carries the meaning” of both of these words. A sculptor and a sculpture both have a relationship in meaning to the free base <sculpt>.

And what changes in the spelling is the suffix. In <sculptor> there is a suffix <or>. This is called the agent suffix and when added to a word it shifts the sense to “someone or something that does something.” We see the same agent suffix in words such as <actor, navigator, inventor>. This suffix has a grammatical force. Words ending in the agent <or> suffix are nouns.

The word <sculpture> has a suffix <ure>. This suffix also indicates a noun, but with a different sense. This suffix is also found in nouns such as <nature, lecture, nurture, pleasure, seizure>.

If the premise that spelling is essentially speech written down were true, then we would be seeing different spelling when the pronunciation changes. We don’t see that.

If the premise that spelling is essentially speech written down were true, then we would be seeing the same pronunciation of the <t> in all of these words, when we change only a suffix. We don’t see that.

Those who argue that spelling is speech written down make that claim by laying out evidence using only simple words where there is no change in a pronunciation as we add a suffix, words such as <playing/player, stretching/stretched>.

But then they run into <say & says> and they declare that <says> is an irregular spelling. The spelling of <says> is clearly very regular:

play + s ➞ plays

lay + s ➞ lays

say + s ➞ says

The pronunciation of <says> doesn’t fit this hypothesis that spelling represents pronunciation directly, but rather than go back and re-evaluate that hypothesis, words such as <says> are simply declared to be irregular. That is not science, as Pete Bowers has been saying for more than a decade.

So I’ve just shown you evidence from one pair of words, where we see spelling remaining constant in order to represent a unit of meaning consistently in every word derived from the same base. There is more evidence for this feature of the English writing system everywhere you look. This same pattern is in words like <capture/captor, lecture/lector>. But we see changes in pronunciation without accompanying changes in spelling in so many other word families. We’ve just talked about say/says> and here are more examples with <cave/cavity/excavate, heal/health>. You’ll see this everywhere in English spelling, once you start to look.

The spelling of words makes perfect sense, but the purpose of spelling is NOT primarily to represent pronunciation. The relationship between written and spoken language can only be understood in the context of morphology and etymology.

Please contact me here with your questions, comments, and reactions.